600 men dead? The Uncertain History of Professional Poisoner Giulia Tofana

- Jasmine Fry

- Aug 6, 2025

- 5 min read

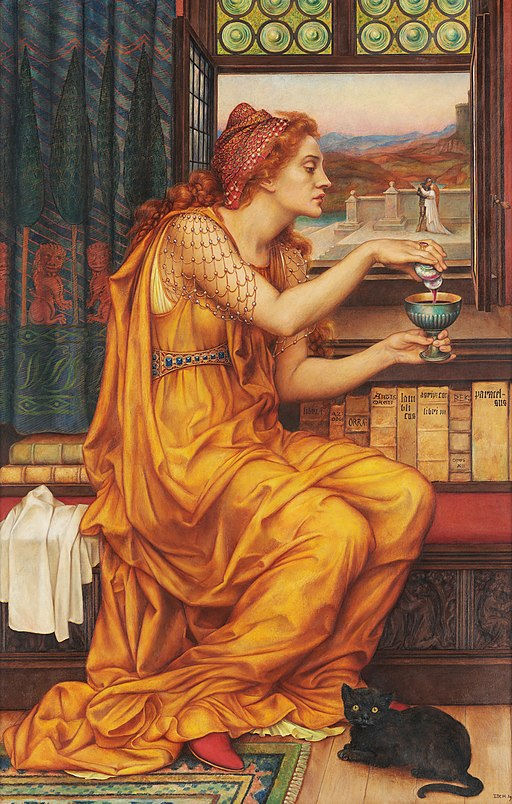

Giulia Tofana was a professional poisoner in 17th-century Italy who was convicted of killing over 600 men. She provided a deadly poison to women who needed to escape from loveless and abusive marriages which left their husbands dead and doctors thinking they perished from natural causes.

However, whether Giulia, or her poison, Aqua Tofana, ever truly existed, is a mystery. She became a legend. A threat, a murderer. A heroine, a saviour.

Scholarship is few and far between concerning Giulia. However, fiction writers have been inspired by her tale. I recently read The Poisoner’s Tale by Cathryn Hemp, which I would definitely recommend. The reason I know of her existence is my work on a short film loosely inspired by her, The Lace, which has motivated me to research Giulia and the history of female poisoners further. Online articles abound concerning her and she is discussed on social media sites, which shows that while the hard facts surrounding her may be few, there’s something about her story that grips normal people and history-lovers.

The Tale of Giulia Tofana

Giulia’s story – how true or manufactured it is – goes something like this.

She was born in Palermo in Sicily in 1620, the daughter of Thofan ia d’Adamo, a poisoner who was hanged in 1633 for the death of her abusive husband, Francesco. After which Giulia fled the city and went first to Naples, and then to Rome.

In both cities, she sold her poison, Aqua Tofana. Later in Rome, she worked alongside a circle of trusted women which included her daughter, Girolama. First concocted by her mother, Aqua Tofana contained lead, belladonna and arsenic, and was, at the time, a traceless poison. The poison was first recorded in the early 1630s, and it was sold masquerading as cosmetics or vials of holy oil, known as Manna of St Nicholas, through her apothecary.

Giulia’s dispensing of her Aqua was meticulous. It was not available for regular purchase as customers had to be referred or vetted to have access. The poison was to have access. The poison was known to be used by women who desired freedom from men in their lives, particularly cruel husbands. It was administered in three doses in order to mimic a steady de cline in the victim, all the while the assailant would express worry and concern for their worsening condition as if it was an ordinary sickness.

Unsurprisingly, women weren’t having the best time in 17th century Italy. Girls, especially nobles, were sometimes married young and divorce would not be fully legalised in Italy until 1970. Women’s rights also decreased in marriage and they relied heavily on men for financial support. As J.E. Shaw notes in Women, Credit and Dowry in Early Modern Italy (2018). “[women were] obliged to entrust their fortunes to the care of men: to husbands in the form of the dowry, to sons in their business ventures, to governments through investing in public debt, and to merchants, shopkeepers and craftsmen as equity investors.” Only in widowhood could women gain more control of their money, which made it more desirable for unhappy wives...

Aqua Tofana was a great success, and as mentioned, Giulia was suspected of killing 600 men or more in the 1630s to 1650s. Her success, however, was not to last. One wife had slipped some Aqua into her husband’s soup – one dose of the three needed to finish him off – but when he went to eat it, she abruptly stopped him. Questioning why his wife would so vehemently tell him not to touch his dinner, he forced a confession out of her. Giulia and her circle of poisoners were hunted down by the Papal authorities, Giulia claiming sanctuary for some time within the walls of a nunnery.

Yet, she would eventually be caught, tried, and sentenced to death. In 1659, with her daughter Girolama and her closest associates, she was publicly hung in the Campo de’ Fiori. Pamphlets distributed at the event defaced the terrible and cruel Giulia Tofana and her followers as murderers and witches.

How much of this is true is unknown. The date of her death is usually cited as 1651 but the date of the execution of her associates was recorded as 5 July 1659. Some accounts even place her death into the 18th century. The confusion 19 with the date 1659 is likely since there was the documented Spana Prosecution that occurred in 1659-60, which concerned a circle of poisoners, including Girolama and the Aqua poison, but not necessarily Giulia Tofana herself.

Giulia’s relation to her alleged mother and daughter has been questioned: the year of her birth, her name, and sometimes even her existence. In connection to the Spana Prosecution, it seems likely that Giulia’s (likely step) daughter, Girolama Spara (who is also known by a variety of names), has had her story in part mixed and confused with that of Giulia’s. In my research, I’ve also not found much evidence of the soup incident so that may merely be part of the myth. Historians have noted that since the Aqua poisonings in the mid-17th century, the story has been spun into sensationalist stories which continue today in the form of true crime fans on podcasts and short-form content in various corners of the internet.

Giulia’s Legacy & Female Poisoners

On Mozart’s mysterious death in 1791, he claimed to have been poisoned: ‘I am sure that I have been poisoned. I cannot rid myself of this idea... Someone has given me Aqua Tofana and calculated the precise time of my death.’ Aqua was made into myth, one that struck fear into the hearts of men.

Giulia is not a solitary figure. Countless women across history used poison to murder their husbands or others who stood in their way, whether proven or alleged. Infamous poisoners include Lucrezia Borgia (Italian, 1480-1519), Ranavalona I (Madagascan, 1778-1861), Marie Lafarge (French, 1816-1852) and Mary Ann Cotton (English, 1832-1873), among many others.

There’s a popular idea that ‘poison is a woman’s weapon’. Brute force is not necessary to administer it, and it’s a more covert, secretive method. Unsurprisingly, in actual modern statistics however, men are far more likely to be poisoners, but it doesn’t stop this image being a popular one. Historian Daniel Kevles in his Slate article Don’t Chew the Wallpaper: A history of poison calls poison ‘a great equalizer’, continuing, ‘murder required administering a poison in repeated or large doses, tasks that women could conveniently perform since they were trusted with the preparation of food and the administration of medicines’. To day, female killers are more likely to use poison than a man (as male killers greatly favour guns) and yet the idea of the female poison er is particularly potent. As Liza Perrin argues in The League of Lady Poisoners (2023), this is ‘not really about the fear of poison so much as about the fear of women – especially women who under mine feminine roles and challenge society’s order.’ This is in part why female true crime fans eulogise her so greatly.

It is of course frustrating that Giulia’s history is not confirmed. Details of women’s lives were so often lost to history; sometimes only records of the man they married left to prove their existence.

But with Giulia’s tale we should comfort ourselves of its uncertainty. Mozart whispered the name ‘Aqua Tofana’ on his deathbed, actual poison conspiracies were fervent in 17th century Europe, endless accounts of women across the centuries have used poison to kill, and true crime girlies on the internet are trans fixed by Giulia’s murderous path, fictional, or not.

And does it not seem fitting for Giulia, an administer of poison – that elusive, shadowy killer of men – to be similarly lost in the records?

Written by Jasmine Fry (23-24 Historia Editor) English & History Graduate.

Issue 15, Historical Mysteries, Autumn 2024.

Jasmine Fry is an English and History graduate and was the 23/24 Editor of Historia. Currently, she is working on a period short film inspired by Giulia Tofana’s legend, set in the golden age of poisoning, the Victorian Era.

Comments