A Witchy Mystery: The Root of Hysteria and Injustice in Salem

- Charlotte Reid

- Aug 6, 2025

- 5 min read

In 1692, Salem Village found itself at the centre of an infamous case of mass hysteria. After eight young women accused their neighbours of witchcraft, trials ensued and, when the episode concluded in May 1693, fourteen women, five men and two dogs had been executed for their supposed supernatural crimes. These notorious events in Salem were merely one chapter in a long story of witch hunts taking place in Europe and the Americas between the 14th and 18th century. It is generally believed that some 110,000 persons in total were tried for witchcraft and between 40,000 to 60,000 were executed.

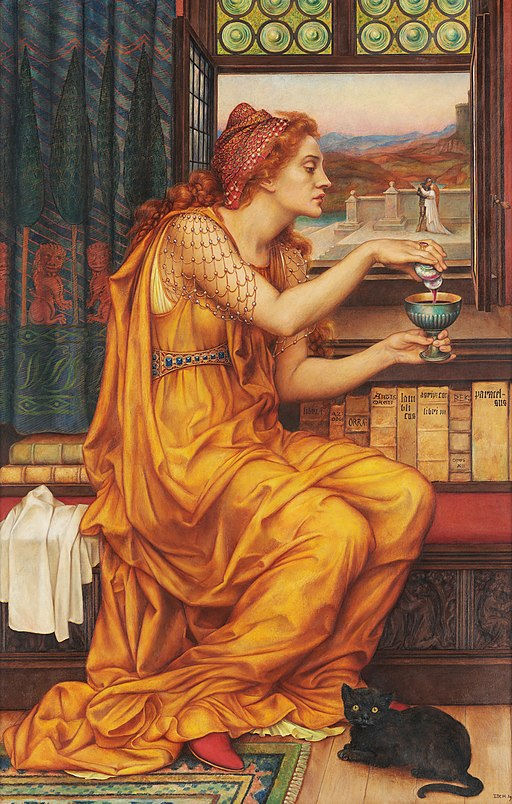

Witches were thought to be followers of Satan who had traded their soul for his assistance. among historians: what could cause such a destructive lapse in due process? Many different theories exist, from economic deterioration to an outbreak of disease, proving Salem maintains a strong foothold in our collective history. It was believed that they employed demons to accomplish magical deeds, that they could change form, that animals acted as their familiar spirits, and that they rode through the air at night to secret meetings and sinful entanglements. Undoubtedly, some individuals did worship the devil and attempt to practice sorcery, but no one ever truly embodied this concept of a witch. Thus, identifying witches was done through suspicions or rumours, fostering a never-ending cycle of false accusations, convictions and executions. The witch trials in Salem have been explained as the result of church politics, family feuds, and European witch hunt fervour, all of which unfolded in a vacuum of political authority. But the mystery remains debated.

Emily Oster’s theory attributes the witch trials to a “little ice age” which lasted from 1550-1800 and caused economic decline and food shortages. Temperatures reportedly began to drop at the start of the 14th century, with the coldest periods occurring from 1680 to 1730, which overlaps with the events in Salem. Anti-witch fervour among communities in Europe and the American colonies was encouraged by this misfortune as people were powerless to stop it. Economic hardship and a slow down of population growth may have caused widespread scapegoating which manifested itself in persecution of supposed “witches”. After all, it was widely accepted that witches existed and could control natural forces.

Another socioeconomic theory comes from Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum who have suggested that tension between two groups was the reason for witchcraft accusations. Salem Village, where the accusations began, was an agrarian, poorer counterpart to the neighbouring Salem Town, populated by wealthy merchants. Salem Village was being torn apart by feuding groups – agrarian townsfolk to the west and more business-minded villagers to the east, nearer to the Town. Boyer and Nissenbaum explain that as tensions unfolded, “they followed deeply etched factional fault lines, influenced by anxieties about accessing the political and commercial opportunities in Salem Town.” This growing hostility pushed western villagers to accuse their eastern neighbours of witchcraft. However, critics of this theory have argued the map used was highly interpretive and considerably inaccurate; that there was no significant east-west division between the accusers and the accused, nor between households of differing economic status. Theories of neighbourhood disputes are plentiful though, as historians have often attested that a rivalry existed between Salem’s two leading families, the Porters and the Putnams.

Another divisive issue in Salem was the result of Church poli tics. In 1689, Samuel Parris, a merchant from Boston, became the pastor of the village’s congregational church. Relatively soon into his tenure he sought greater compensation, including owner ship of the parsonage, which did not sit well with many members of the congregation. Parris’s Puritan theology and preaching also divided the congregation into pro- and anti-Parris factions. It was Parris’s daughter Betty (age 9), his niece Abigail Williams (age 11), and their friend Ann Putnam, Jr (age 12) who began exhibiting increasingly strange behaviour in 1692. They screamed, made odd sounds, contorted their bodies and complained of pinching sensations. The behaviour mirrored that of children from a family in Boston believed to have been bewitched, described in Cotton Mather’s book Memorable Providences, Relating to Witchcraft and Possessions (1689), which may have been known to the girls in Salem. Some historians have stated the behaviour is better understood as juvenile delinquency, but, at the time, the local doctor was unable to account for their behaviour medically and placed the blame on the supernatural instead.

Pressured by Parris to identify their tormentor, Betty and Abigail claimed to have been bewitched by Tituba, one of the family’s slaves, along with two other marginalized members of the community, Sarah Good and Sarah Osborn, both of whom didn’t attend church regularly and were scorned for romantic involvements. Initially all three women protested their innocence but after repeated questioning, Tituba, likely fearful due to her vulnerable status as a slave, told the magistrates she had made a deal with the devil. This confession was accepted as evidence that more witches existed in the com munity, and so hysteria mounted.

T he fits and strange behaviour that were reported have since become the focus of some scholars who have used modern science to suggest physiological explanations for the witch trials. Linnda Caporael argues that the girls suffered from convulsive ergotism, a condition caused by a type of fungus found in rye and other grains. It produces hallucinatory, LSD-like effects in the afflicted and can cause victims to suffer from vertigo, crawling sensations on the skin, extremity tingling, headaches, hallucinations and seizure-like muscle contractions. With rye being the most prevalent grain grown in the Massachusetts area at the time, combined with its damp climate and long storage period, an ergot infestation could have occurred. With doctors unable to find an underlying physical cause for these symptoms, they concluded that their patients suffered from possession by witchcraft, a common diagnosis of unseen conditions at the time.

Economic and physiological explanations aside, those executed during the Salem witch trials were victims of intense paranoia, misdirected religious fervour and a justice system that valued repentance above the truth. The Puritan settlers who founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony were deeply religious, and their belief in witches was not unique. Numerous challenges in their new home, alongside a strict religious code, created a climate ideal for fear and suspicion to grow. It was a community vulnerable to witchcraft accusations, but can this tragic episode in American history be understood as the product of strong belief? Certainly prejudice, misogyny and the dangerous abuse of power also came into play.

In Salem, 14 of the 19 people found guilty of witchcraft were women, and during the regular witch trials throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, women vastly outnumbered men in the ranks of the accused and executed. The few men tried for witchcraft were typically associated with alleged female witches, often their husbands or brothers. Within deeply religious Puritan communities, women held a powerless position and were expected to observe model Christian subservience to their husbands. Puritans also believed women more likely to be tempted by the Devil, recalling the story of Adam and Eve. Since the magistrates, judges and clergy were all men, it was men who enforced the rules and exclusively held power. When a woman stepped outside her prescribed role, she became a target. Therefore, Salem’s witch hunt was the result of a patriarchal society, driven by a justice system that escalated local grievances to capital offences, and targeted a subjugated minority.

Ultimately, the Salem Witch Trials remain one of the most troubling events in American history, serving as a potent reminder of the importance of critical thinking, evidence-based reasoning, and the protection of individual rights in the face of social pressure. As we reflect on the trials centuries later it is crucial to remember that lives were lost and families devastated because of the failure of due process, as well as unchecked fear and intolerance.

Written by Charlotte Reid (24-25 Editor-in-Chief) 2nd Year History

Issue 17, Historical Mysteries, Autumn 2024.

Charlotte Reid is a second year History student and the current editor of Historia. Her interests include mythology and the impact of religion upon society and community identity.

Comments